Method 'Practical Logic':Principles of ModelingPossibilities of Knowledge, Information, and Logic.

C.P. van der Velde.

[First website version 04-01-2005;

sixteenth, revised version 10-12-2019] Table of ContentsIntroduction. 1. Knowledge as a Life Necessity. 2. The Importance of Reliable Guidelines. 3. Modeling. 4. The Model Serves the User. 5. Fallibility of Knowledge. 6. Postmodern Skepticism. 7. Limits to Relativity. 8. Objectivity as an Aspiration. 9. Additional Criteria for the Social Sciences. IntroductionOur lives are increasingly dominated by information, knowledge, and technology. At the same time, qualitative developments in science and technology, particularly in the exact sciences, are constantly occurring. Insights and applications that seem advanced today are often surpassed the next day by improved versions and superior innovations. Because knowledge has so often proven fallible or improvable, philosophers have wrestled since early antiquity with questions about the nature of human knowledge and judgment. In epistemology, philosophy of science, or epistemology, countless views and theories have been produced about the possibilities of obtaining 'knowing', ' truth', and 'certainty', and about the scope of human cognitive ability. It is not always clear what goal these thinkers and authors have in mind with all these intellectual constructs. The general tenor seems to be to declare any notion of 'certain knowing' a dangerous illusion. In any case, when the goal is to improve the quality of information processing and judgment, it is useful to consider the feasibility of knowledge and the limits of judgment. Below, we will therefore review several different perspectives, illuminating the possibilities of knowledge and information from various angles. Attention will be paid to the antecedents, arguments, and rationales of these views, their mutual historical, cultural, and logical relationships, as well as the consequences in both logical and practical terms, both favorable and less favorable. This discussion ultimately leads to several conclusions that together form a solid and nuanced vision of knowledge and information. This provides a framework for a methodology to optimize judgment, particularly for result-oriented applications, and especially for the social sciences. 1. Knowledge as a Life Necessity

(1.1)

A Material Living World.Most people agree that we do not simply float around in a vacuum, but live in a specific environment, a concrete reality. This is characterized by matter, energy, time, and space, and is therefore physical in nature. We can assume that it largely exists 'in itself', An Sich, independent of our perception, knowledge, or awareness of it. For this reason, we can call it an ' objective' reality. The assumption that an independent reality exists (so-called realism, or objectivism ) has been contested by numerous philosophers in East and West since antiquity. After all, no completely conclusive and definitive proof can be found for it.

(a)

Not Directly Knowable.Consider Plato's metaphor of the Cave, where people are imprisoned for life: with only 'shadows on the wall' as meager, indirect reflections of reality - a prison of ignorance (Socrates' argument in Plato's Republic, 7.514a ff.). "The idea that reality depends on who perceives it dates back to Plato. I’m amazed that young people at universities keep coming up with this idea as if it’s revolutionary. It infects political discourse." (Derk Walters, 'I’m Afraid of a Civil War', quoting Susan Neiman (1955), philosopher; NRC, November 3, 2017) . (b) Only Selectively Knowable.Or consider the Indian metaphor, described among others in the oldest Buddhist scriptures, of blind people touching an elephant, each highlighting a different aspect, but unable to grasp the whole in any way (e.g., the Tipitaka, 2 Sutta Pitaka, Khuddaka Nikaya, Udana 6.4, Tittha Sutta). (c) Existing Only in Perception.The other extreme is the idea that every notion of 'reality' exists solely in our own mind, or at least perception (so-called idealism, subjectivism), without any substrate or reference outside it. This assumption has enjoyed great popularity worldwide in recent decades, since the rise of postmodernism.

{Note: Upon closer inspection, however,

this idea leads to all sorts of insurmountable contradictions with everyday human experiences,

needs,

and motives: no representation or expectation regarding a reality beyond immediate here-and-now impressions would then have any predictive value.

This is why even its adherents rarely or never consistently adhere to it in their daily lives.

At least,

they strikingly often behave as if they do believe reality has some substance.

Moreover, the idea implies rather absurd assumptions like solipsism, from which various other unsolvable paradoxes arise, as we will see later.} (1.2) Subjective Starting Points.Within the external reality, we strive to meet our most important needs and interests. These revolve primarily around survival and well-being (experiencing happiness) - for ourselves and together with others. Thus, we function within the physical reality from our subjective experience and goals. This means we can notice or experience things subjectively and recognize them as such, without necessarily or exclusively needing an objective justification for it. These are also regarded as pre-scientific, 'intuitive', or 'naive' experiential data.

{Note: This does not necessarily mean that such subjective experiential contents have no basis, origin,

or cause (a so-called correlate) in objective reality, such as the nervous system, senses,

or immediate environment.}

(1.3) Need for Knowledge.It turns out that to achieve our subjective goals, we are heavily dependent on our environment. We therefore need knowledge about reality as a guide to survive and function in the world. 2. The Importance of Reliable Guidelines

(2.1)

Information as a 'Signpost'.To achieve our objectives, it is often necessary to steer or at least adjust circumstances and events - and thus influence them in some way. Such a situation generally has two sides:

(I) There is a current state with which we are not, or no longer fully, satisfied; and

These states can pertain to external and internal matters, material and immaterial aspects. In any case,

we usually assume that some aspects of state A have a certain 'mapping' (or correspondence),

direct or indirect, to some aspects of state B.(II) There is a goal we want to reach: a desired state. (2.2) Guidelines for the Route.Given this general structure of a situation, the question is: how do we get from A to B? Usually, there are many different possibilities for behavior and response in a situation. But our more general goal is to act and decide effectively in various situations. Preferably, we take the shortest, easiest, and most advantageous route. This means we need guidelines to determine our actions and decisions: in other words, information. Specifically, a representation of both A and B, as well as the paths between them. (2.3) Information for Predictions.To know which route offers the best chances and advantages to achieve our goal in different situations, it is useful if we can anticipate and respond to what is happening in the world. This means, in particular, that we must be able to predict how our actions will play out in our living world; in other words, how things, animals, and people will react to our actions. (2.4) No Direct Access.In short, we will need some reliable knowledge about the world and the 'objects' within it. At the same time, however, we have no direct access to the external world. After all, we can only notice something about that outside world through our own subjective experience of it. (2.5) Knowledge About Knowledge Needed.Useful knowledge, or information, is therefore not something that is always readily available. It is therefore helpful to know how to find and recognize useful information. 3. Modeling

(3.1)

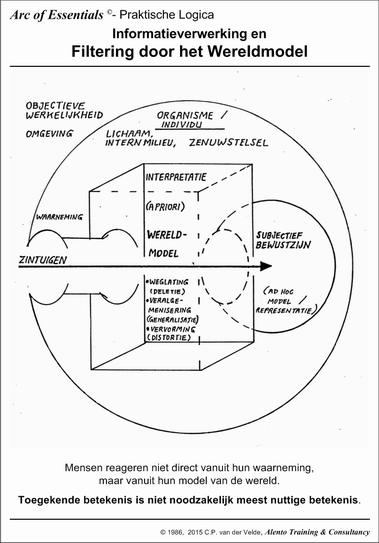

The World Model.To continuously gather information about the situation we are in, the goals we have, and the possibilities to achieve those goals, nature has equipped us with senses and a nervous system. With these, we try to form a representation of our living world: a world model. This worldview includes aspects such as life philosophy, view of humanity, self-image, body image, etc. " A person's processes are psychologically channelized by the ways in which he anticipates events. " (Kelly, G.A., 1955; 'Theory of Personal Constructs', 'Fundamental Postulate'). "We anticipate events by construing their replications. " (Kelly, G.A., 1955; 'Construct Theory', 'Construction Corollary') . (3.2) Different Terms for the World Model.The concept of a 'representation of the world' can be found under various names in numerous theories across different scientific fields - for example:

(a)

In Psychology.

(·) Secondary Signal System (Pavlov, 1849-1936)

.

(·) Self-Image and Ideal Image (Rogers, 1951) . (·) Schemata (Piaget, 1952; Neisser, 1976; Rumelhart, 1980) . (·) Personal Construct System, or Structured Network of Pathways; in 'Construct Theory' (Kelly, 1955). (·) Belief System; in Rational-Emotive Therapy (Ellis, 1955) . (·) Implicit Personality Theories (Bruner & Tagiuri, 1954) . (·) Hypotheses (Bruner, 1957). (·) Mental Picture, Cognitive Map (Tolman & Holt, 1958) . (·) Inferential Sets (Jones & Thibaut, 1958). (·) Generalized Reality Orientation (Shor, 1959) . (·) Plans of Action (Miller, Galanter & Pribram, 1960) . (·) Cognitive Orientation (Kreidler & Kreidler, 1972a, 1976, 1981) . (·) Theories (Epstein, 1973). (·) Mental Sets, Learning Sets (Erickson, Milton H., Rossi, Ernest L., & Rossi, Sheila, 1976). (·) Scripts (Abelson, 1976; Schank & Abelson, 1977) . (·) Prototypes (Cantor & Mischel, 1977). (·) Coherent Reality Construction (Boekesteijn, 1981) . (·) Information Coding System, or Human Software; in Cognitive Psychology (e.g., Simon, 1985). (·) Cognitive Code (Best, 1992). (b) And Beyond Psychology.

(·) Weltanschauung, Worldview; in philosophy (e.g.,

Kant (1724-1804), 1790; Schopenhauer (1788-1860), 1818; Frankl, 1973; Duijntjer, 1974)

.

(·) Weltbild (Lange, 1936). (·) Doctrine, Dogma; in theology (e.g., St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430), ca. 397; Milton (1608-1674), ca. 1670). (·) Ideology (Destutt de Tracy, A.L.C., 1796) . (·) Knowledge, Theory, Hypothesis, Model, Paradigm, Research Program; in epistemology (e.g., Popper, 1934/1959; Kuhn, 1962; Lakatos, 1968, 1970). (·) Engrams; in neurophysiology (R.W. Semon, 1921; K.S. Lashley, 1929). (·) Symbolic Representation or Map; in General Semantics (Korzybski, 1921, 1933, 1948, 1958). (·) Symbolic Universe; in information philosophy (Cassirer, 1954) . (·) Knowledge of the World; in General Linguistics (Semantics), (e.g., Leech, 1974); and Computational Linguistics (Parsing) (e.g., King, ed., 1983). (·) Frames (Minsky, 1975). (·) World Model; in the communication model Neuro-Linguistic Programming (Bandler & Grinder, 1975/1977). (·) Stylized Version of the World, or Semantic Net; in Artificial Intelligence (esp. Knowledge Engineering), (e.g., Charniak & McDermott, 1985) . (3.3) Basis of Functioning.The world model - the entirety of perceptions and concepts - is then the 'version' of reality we use to determine our responses. " People react primarily from their inner representations and not from their sensory perceptions of events. " (Lankton & Lankton, 1983) . "We respond toward any situation or object in terms of its meaning, as we interpret it." (Lowery, S.A., & DeFleur, M.L., 1988, p.28). "We do not react directly or immediately to the world, but we operate within that world through a 'map' or model (a self-created representation) of that world to guide our behavior in it. " (Bandler & Grinder, 1976, p. 17) . " People do not directly respond on basis of their sensory experiences of events but primarily from their internal representations" (Lankton & Lankton, 1983). "We are not upset by things, but by our thoughts about those things. " (Epictetus, 55-138 AD, 'Encheiridion').

{Note: Obviously, there are many factors determining psychological functioning.

For a realistic and purposeful classification of these factors, closely aligned with the structure and functioning of the nervous system: See the 'Ten Factors Model' © of human functioning.} 4. The Model Serves the User.The relationship between human knowledge and reality is comparable to that between a map and the area it depicts.

(4.1)

The Map Is Not the Territory.In our reality, much is uncertain, except perhaps the basic rule: the representation of reality is not reality itself, or the principle of Non-identity, in the well-known metaphor: the map is not the territory ("The Map is not the Territory", Alfred Korzybski, 1933). (4.2) Priority to Utility Value.'Absolute' objectivity is fortunately not really necessary, because the primary function of our knowledge is not 'truth', but usability to achieve our everyday goals, in other words: effectiveness. It is thus primarily about utility value, and only secondarily about truth value. "Nothing is as practical as a good theory." (Van den Hout, 1997; 'Theories Considered'). This view is found in currents of (philosophy of science) that emphasize the practical usability of knowledge ( pragmatism), utility and advantage (utilitarianism), and mediating role (instrumentalism ); see especially American philosophers like Charles Sanders Peirce, John Dewey. (4.3) Knowledge as a Guide.On this point too, there is a similarity between human knowledge and a map: the map may represent a far-reaching reduction of the depicted area, but it does not need to be a one-to-one representation: it serves primarily as a guide, signpost, or guideline for our actions and decisions in the realm of reality. " It must be kept in mind that the entire world of representations in its totality is not intended to be a depiction of reality - that would be an impossible task for it - but an instrument with which we can more easily find our way in the world. " (Vaihinger, 1924, p.15). (4.4) Utility Value Depends Primarily on the User.The utility value a model has for someone obviously depends on the goals the user has in mind beforehand, as well as the findings they gain from applying it. For example, an architect has different requirements for a blueprint than a pilot, a hiker different ones than a motorist. Generally, however, it holds that beliefs and ideas are valued according to whether they deliver the hoped-for outcomes. In other words, " just in so far as they help us to get into satisfactory relations with other parts of our experience. " (James 1991:28). " The extent to which the structural similarity between a model and the depicted object is significant and relevant is determined by the subjective choices of the observer." (Les Tombes, 1974; Meerling, 1981, p.36). 5. Fallibility of KnowledgeDaily experience teaches us that information can be helpful in fulfilling our goals and interests, but also confusing or even misleading. That information represents something is thus independent of the degree of its substantive reality content. Because we have a great stake in reliable knowledge, the crucial question is how we can obtain it - and first of all: to what extent is that possible? The 'naive' view of the concept of 'truth' is that it can be a property of beliefs or statements, in the sense of their degree of correspondence with a state of affairs in reality. "The popular notion is that a true idea must copy its reality. " (James 1991:88). If we take this view entirely literally, then the truth value could be an inherent property of some beliefs or statements, which is moreover absolute and 'timeless ': constant and definitive. In this view, science, research, and theorizing have the task of bringing ideas and statements ever closer to 'the truth': that of the 'complete reality'. Through a gradual process of trial and error, growth of knowledge becomes possible. " For 'truth' sounds like the name of a goal only if it is thought to name a fixed goal - that is, if progress toward truth is explicated by reference to a metaphysical picture, that of getting closer to what Bernard Williams calls 'what is there anyway'." (Rorty 1998:39). On this path, however, we encounter several obstacles.

(5.1)

Our Cognitive Capacity Is Limited.One difficulty is that 'the' reality is almost infinitely vast, complex, and unpredictable. Compared to this, our capacities for perception, understanding, and knowing are relatively extremely limited and fallible. (see, among others: Wehl, 1927/1949, p.83, 116; Korzybski, 1933; Popper, 1934/1959, p.111; Lakatos, 1970; Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky, 1982).

{Note: See also the overview:

Limitations of Human Knowledge and Judgment.}

(a)

Everything Is Changeable.The inescapable changeability and impermanence of the material world were emphasized, for example, by Heraclitus, with the principle 'Everything flows', or 'everything is in motion' (panta rei; Heraclitus of Ephesus, Greek philosopher, 6th century BC ). The practical consequences of this insight were also recognized early on: " You can never step into the same river twice, for it is always fresh water flowing toward you. " (Cratylus, student of Heraclitus); " Nothing ever is, but everything becomes." (Plato); " Nothing is steadfast." (Aristotle) . (b) Everything Is Transient.Especially Eastern thinkers pointed early on to the transience and relativity of the world of phenomena, or all that is 'formed'. The renowned Buddha (also known as Siddhartha Gautama, Shakyamuni Buddha, etc., ca. 563-480 BC) set in motion what is known as the 'wheel of truth' with the following words: ' What is subject to arising is subject to ceasing' (" Yam kiñci samudaya dhammam, sabbam tam nirodha dhammam "), Tipitaka, 2 Sutta Pitaka, SN Samyutta Nikaya, 5 Maha Vagga, 56 Sacca-samyutta, Sutta 11: Dhamma-cakka-ppavattana Sutta, 'The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of Dharma').

{Note: The apparently universal changeability of phenomena - both physically empirical and subjectively perceptual

- does not necessarily constitute an absolute barrier to knowability. Of course,

circumstances change constantly, the content varies continuously; but the underlying

structure proves, at least in the physical domain,

quite robust and has also proven knowable to some extent in terms of provable regularities.}

(5.2) 'Absolute' Objectivity Is Impossible.It is clear that no representation of reality can achieve perfect correspondence, in the sense of complete symmetrical equivalence, structural identity, or isomorphism .

{Note: Perfect correspondence amounts to a symmetry with correlation = 1.0.}

" No one’s understanding will ever fully correspond with the world outside." (Bandler & Grinder, 1982, p. 40). "The world is such a maze of things, so complicated, that no statement is complete." (Stephan Themerson, 1910-1988). " There is a necessary difference between the world and any individual model or representation of the world. " (Bandler & Grinder, 1975a/1977, p. 20) . Human 'knowledge' about reality is thus always subjective, relative, and imperfect: incomplete, and to some extent inaccurate, arbitrary, and biased. "All science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike. " (Albert Einstein, quoted in: 'The Expanded Quotable Einstein', 2000) . (5.3) Hypothetical Structure.We can never conclusively prove that any structure we know or suspect actually exists in the 'outside world' in exactly the same way we think it does. Structural features can thus never be directly observed or demonstrated in the outside world: they involve at most pseudo-inherent structure. All structure we know thus remains an assumption that is fundamentally fallible, provisional, and of an exploratory, tentative nature. For these reasons, human knowledge can never attain the status of 'certainty', 'truth', or 'probability' - at best, that of 'expectation', 'suspicion', 'assumption', 'accepted assumption', 'belief', 'conviction', or 'faith'. In short, it is always hypothetical in nature. "Our knowledge is never absolute but always swims, as it were, in a continuum of uncertainty and of indeterminacy." (Peirce, Ch.S., 1931-1958: 171). "Man's truth is never absolute because the basis of fact is hypothesis. " (Peirce, Ch.S., 1857-1866, Writings vol.I, p.7) . (5.4) Provisional Nature.Even the edifice of scientific knowledge, according to philosopher of science Karl Popper, as described in his epistemology of critical rationalism, has only a provisional justification, based on pragmatic considerations that are always context-bound. " The empirical basis of objective science has thus nothing 'absolute' about it. Science does not rest upon solid bedrock. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles. The piles are driven down from above into the swamp, but not down to any natural or 'given' basis; and if we stop driving its piles deeper, it is not because we have reached firm ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that the piles are firm enough to carry the structure, at least for the time being." (K.R. Popper, 1934/1959, p. 111). The concept of 'truth' can therefore, according to more modern views of science, better be replaced by ' verisimilitude' (verisimilitude) (ibid) . The view in (philosophy of science) that emphasizes the inevitable fallibility of all human knowledge, fallibilism, has a long history. Thus, in (Western) antiquity, there existed the current of skepticism, to which the Greek philosopher Pyrrho, among others, is counted.

{Note: {

Caveats.Nevertheless, this proposition carries some paradoxes:

(a) The proposition states that certain knowledge does not exist,

while simultaneously asserting this as a certainty.

} Taken in a strict and absolute sense, this principle thus leads to a paradox in its generality. (b) Karl Popper proposed as a solution that this principle should be regarded as conditional and provisional true or certain, as long as the opposite has not been proven. However, this seems to me a pseudo-solution, as it introduces circularity.

(b1) An extremely general proposition like this will, according to fallibilism,

be conditional, fallible, and provisional. It must therefore, in line with Popper’s own

falsification principle, be refutable. For that, it must logically be testable,

thus 'open' to a possible counterexample (contraindication, falsifier).

This is obviously all contrary to the fundamental criteria for scientificity that Popper himself proposes.

Again, a paradox - thus Popper’s solution to the earlier paradox collapses.(b2) Such a counterexample can only be a specific (substantive) proposition. To be recognized as a 'real' counterexample in this context, it must, perhaps after surviving critical discussion, ultimately be able to be accepted as certain. Beforehand, however, it can - again according to the same view - only be accepted as conditional (i.e., relative) and provisional true or certain. (b3) But from a combination of two instances of 'uncertain', nothing can follow that is 'more certain' than the premises. This follows, among other things, from the principles of probability theory, Boolean logic, modal logic, etc. The result of the confrontation (the conjunction) of multiple propositions is not the sum, but the product of their probability or truth values. With premises that are less than 100 percent certain, the conclusion will therefore always have the lowest value. The outcome can thus never surpass or 'displace' the original in certainty (indeed, it will be eliminated by the logical mechanism of transferential equivalence reduction). It can therefore never serve as a 'better' belief than the original. And thus, the proposition proves not falsifiable, but invincible, and therefore not provisional but definitive. (b4) With this 'solution' that Popper proposes for the earlier paradox, he thus ensures a tautological confirmation, an immunization, of his own proposition. (c) One way to circumvent both paradoxes is to explicitly introduce the presupposition that certain knowledge can, after all, exist. The proposition could thus be better nuanced as: we cannot (i.e., never) assume that what we currently assume is definitively certain - but we also cannot rule out that we might someday encounter a proposition that is definitively certain. In other words, uncertain assumptions are possible, but certain assumptions are also possible in principle. Admittedly, that is a rather trivial statement. (5.5) Interpretation Is Decisive.The implication of the foregoing is that we cannot know anything about that reality - whether noticing, thinking, realizing, or experiencing - without an active assignment of some subjective structure, in other words, of meaning, on our part: 'You cannot not assign meaning' (Watzlawick et al., 1967/1970). What is decisive for the 'outcome' of our experience of reality is thus not so much the 'true state' of that reality, but our own meaning-making, an active psychological process of interpretation (perspectivism). "We respond toward any situation or object in terms of its meaning, as we interpret it." (Lowery, S.A., & DeFleur, M.L., 1988, p.28). "Neither nature nor history can tell us what we should do. [..] It is we who give meaning and significance to nature and history. [..] Although history has no meaning, we can give it a meaning." (view of Carl Popper, in the words of Herman Van Rompuy, 'Self-Determination Does Not Exist', Trouw, 10-17-2009). (5.6) Structure as Projection.Moreover, all structure we discern in the world has been attributed to it by us beforehand - largely unconsciously - through mental processes of construction, interpretation, and projection. Such a structure is thus, in fact, always an artifact. In other words, knowledge is only possible insofar as the subject’s cognitive capacity allows it. " The meaning an event has for us depends on the frame of reference in which we consider it. " (Bandler & Grinder, 1982, p.1) . " A phenomenon remains inexplicable as long as the viewpoint is not broad enough to encompass the context in which it occurs." (Watzlawick et al., 1967/1970). " If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern. " (Aldous Huxley, 'The Doors of Perception', 1954). (5.7) Inherently Subjective.The above means that all knowledge and information are primarily subject-determined, in other words, inherently subjective. From our perception - within our theory of reality - information can very well be 'purely' objective, meaning entirely independent of any subjectivity. But in fact, when taken literally as 'real' knowledge about reality, it is entirely subjective.

(5.8) A Fundamental Distinction.The so-called 'reality appearance distinction ' thus forms a fundamental gap between the 'external' reality and our inner (conscious) perception. According to some, there is even an unbridgeable gap: one that is absolute, definitive, and insurmountable. " It is impossible to step outside our own framework of thought to view from an Archimedean point whether our own statements accurately describe reality" (Menno Lievers, 'Is This Then the Truth?', 04-15-2006, NRC, p.41) . 6.Postmodern Skepticism.As mentioned, doubts and suspicions about the possibility of 'true knowledge' have existed throughout history. Relatively recent, especially in Western thought, are more radical views on this issue. From the beginning of the twentieth century, a stream of remarkable discoveries and proofs emerged, particularly in the fields of exact sciences such as mathematics, physics, and logic, shaking and often overturning existing beliefs and certainties. The consequences of this extended far beyond the boundaries of those disciplines: they put the prevailing concepts of scientific knowledge and truth itself on shaky ground. In the philosophy of science, there was thus an urgent attempt to formulate an epistemological response to this. Not only did the realization grow that knowledge is always fallible, relative, and provisional. In postmodernism, a stance was taken against the 'old', modernist idea that striving for truth, knowledge, and progress was meaningful at all. In a series of successive views and theories, various 'principled ' arguments were put forward for the position that truth, and thus the growth of knowledge in the usual sense, is an unattainable goal. Not all scientists and philosophers who have spoken out in this vein will unconditionally endorse all the steps of the hard core postmodernists. Postmodernism is, after all, too diverse for that, and in some cases, it must be said, rather muddled. Based on the reasoning of postmodernists, we would expect that little, or rather: virtually nothing, from the outside world - the 'empirical' - penetrates human experience. In other words, the world model would not only be a filter for our direct perceptions but a completely impenetrable 'wall'. In that case, it could not be a meaningful representation of truth or reality, but not only that: it could also have no utility value for dealing with the outside world. 7. Limits to Relativity.The question, of course, is: does anything from the outside world actually penetrate our cognitive capacity? That is, can we ever somewhat get through the 'wall' - or rather, the filter - of our world model? Upon closer examination, there do seem to be limits to relativity.

(7.1)

Information Implies Order.The first thing we can establish is that our thoughts and beliefs can sometimes represent something meaningful. To speak again in terms of the map-territory analogy: the map we use to find our way will not always be just a vague blur or display 'abracadabra'. Without the slightest possibility of knowledge or information, we would forever wander without direction or awareness - through total darkness, a thick fog, or a uniformly colorless plane (it’s hard to imagine). There would then be only total vagueness, noise, and chaos. And that is not information, in the general sense of the word. This means that at the very least, something distinguishable must be present in the representation, so that some difference, however minimal, can be noticed: even if it’s just a dichotomy, like a figure against a background.

{Note: See also: Dimensions of Information

: An analysis of the main views on information.}

(7.2) Utility Value Is Possible via Reference.The relationship between map and territory generally does not take the form of a concrete, direct, singular, physical connection (connectionism). It is more about a relationship of reference. The map offers, as it were, a collection of 'signposts'. To serve a user as such, the map must meet some minimal conditions.

(a)

A Referential Domain Is Needed.A map can only be useful to a user as such if it is clear what referential area it points to. This domain can be of any conceivable nature: it can lie within the general physical reality, but also within someone’s subjective experience or 'Bubble of Perception' (including fantasy, fiction, virtual reality, etc.), and even within the information itself: self-reflexive reference is possible. (b) Possibly (Partly) Unreal.Moreover, a user can find a map very useful even if the entire area it refers to is fictional. It may stem from their own imagination, dreams, or hallucinations, or be derived from external sources like rumors, self-proclaimed prophecies, or collective delusions. For example, a fairy-tale world, a mythology or pantheon, a fictional or futuristic land in literature. (c) Minimally Some Recognizability.Furthermore, for a map to be useful, it must represent something that the user recognizes as referring to the area. We could even say: without recognizability, there is no information. (d) Impossible to Be Fully Unreal.Thus, reference can very well be to something non-existent, something possible, or even something impossible. But even then, the information will usually - to be recognizable as such - represent certain partial aspects that are directly or indirectly derived from properties of already known things. Even if it’s just colors, lines, or shapes - or sounds, smells, tastes, and other physical stimuli - that we (re)know from empirical observations of the world. An interesting phenomenon in this context is abstract art. Typically, it is explicitly not intended to represent things. In visual art, for example, a interplay of line and color can depict shapes and patterns that evoke various impressions and emotions in the viewer. When abstract works have effects, these lie primarily in inner, mental sensations. For instance, 'confusion' or 'curiosity'. But these remain highly individual and hardly predictable. The key here is the psychological mechanism of - 'free' - association. To the extent that recognition emerges in this process, it remains rather diffuse.

{Note: Many artists do want to 'communicate' something with their abstract work to their audience.

But according to very different rules and expectations than usual. Often,

the invitation is not to seek recognition,

but rather to let the work 'sink in' freely and openly, to 'experience' it. Often,

the goal is limited to something like 'raising questions' or 'evoking inquiries'.

The creator/artist may follow some direction in this,

by intending to embed a certain theme or motif in the piece.

The artist may also express a certain 'mood' or 'atmosphere',

through the use of specific stylistic means, line work, and color palette,

and principles of composition and contrast.

Sometimes a hint at the underlying thoughts is given - a 'reference' - through a well-chosen title of the work.}

(7.3) Some Knowledge Proves Adequate.In practice, it turns out that through our perception and thinking, we often succeed, within the context of our goals, in acquiring knowledge that sufficiently approximates reality. We don’t usually bump into every chair we encounter. Our everyday knowledge remarkably often suffices, far more often than we might expect based on chance - say, a 50 percent probability. More generally, living organisms appear to have developed quite ingenious capacities to stay alive, meet their daily needs, and reproduce. These capacities are only possible because they are based on ordered processes, information structures in living cells and tissues. These ordering patterns represent, to some extent, a reflection of aspects of reality - and can therefore be regarded as knowledge. It is evidently possible that a certain degree of structural similarity exists, congruence, or symmetry, between our ideas and reality. Precisely therein lies the function and value of information processing and judgment for the viability of organisms. "A map IS not the territory it depicts, but if it’s good, it has a structure similar to that territory, which determines its usability." (Korzybski, 1958, p. 58-60). We are thus indeed capable of knowledge that is reasonably reliable. Apparently, not everything - knowledge, information, or other data - is merely subjective and utterly relative. It can definitely have something to do with the object, and thus indeed be objective to some extent. (7.4) Knowledge with Long-Term Validity.It turns out that our representation of reality can directly or indirectly reflect regularities in reality that hold over the long term. This yields additional advantages:

(a) This gives knowledge a general validity that extends beyond the original data from which it was derived.

It becomes applicable to multiple situations,

thus gaining a broader scope of application.

And this makes it useful for multiple purposes, in diverse situations.

(b) Through repeated application (replication) of knowledge, it becomes testable against new facts and experiences. "Truth 'means' verification, or if one prefers, verification either actual or possible, is the definition of truth. [..] " Theoretically [..] even such verifications or truths could not be absolute. " [..] "logically absolute truth is an ideal which cannot be realized. " (Dewey, J., 'The Development of American Pragmatism', 1925; 1998a: 7-8). (7.5) Knowledge Implies Predictive Power.Through knowledge, predictions become possible, and with them, bridges to the future. This is undeniably important, because only through this can developments be better anticipated and possibly influenced, redirected, or adjusted in a desired direction, or avoided in time. "What is called 'reason' is long-term foresight. " (Baruch Spinoza). " A person's processes are psychologically channelized by the ways in which he anticipates events. " (G.A. Kelly, 1955; 'Theory of Personal Constructs', 'Fundamental Postulate'). (7.6) A Practical Criterion: Predictive Power.From the foregoing, a simple rule of thumb can now be derived: knowledge, or more generally information, is reliable to the extent that it enables predictions that have not yet been falsified by counterexamples of the predicted events. A very practical definition of the truth content of knowledge is thus: predictive power (see Lakatos, 1968; 1970). " It is the aim of science to establish general rules which determine the reciprocal connection of objects and events in time and space. For these rules, or laws of nature, absolutely general validity is required - not proven. It is mainly a program, and faith in the possibility of its accomplishment in principle is only founded on partial successes. But hardly anyone could be found who would deny these partial successes and ascribe them to human self-deception. The fact that on the basis of such laws we are able to predict the temporal behavior of phenomena in certain domains with great precision and certainty is deeply embedded in the consciousness of the modern man, even though he may have grasped very little of the contents of those laws." (Albert Einstein, Science and Religion, Part II, from Science, Philosophy and Religion, A Symposium, published by the Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion in Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc., New York, 1941. Reprint in: 1994, Ideas and Opinions, p.50). " Theories are blueprints of reality with which you can calculate what happens if you intervene in a certain way. " (Denny Borsboom, psychologist, quoted by Margreet Vermeulen, 'Psychology Is Too Much a Confetti Factory', de Volkskrant, November 24, 2015). "How do you know the table still exists if you go out of the room? Can it pack up and disappear out of the window? Could even pay a visit to the international space station; perhaps even fly to the moon, before it returns to the exact same spot instantly before you re-enter the room? This seems like an unlikely scenario, but one, that we can’t rule out! It is easier to assume that the table stays put when you are not there, that is our best fit model of reality. This is what we do in science; we create best fit models of how we believe the universe actually works " (Stephen Hawking, Grand Design, BBC 2012) . (7.7) Exceptions Can Emerge.Of course, we can always have new experiences that give reason to revise our beliefs. One of the possible contraindications is that of the exception to the general rule. This with the famous comparison by philosopher of science Karl Popper: We can maintain a general rule that all swans are white until we observe a black swan. (7.8) Falsification Is Quite Feasible.In practice, we often find it relatively easy to determine where a representation of things (far enough) departs from the generally recognized, objective, or at least intersubjective reality. We can even gain considerable certainty about the reliability of knowledge when we not only seek confirmation but especially refutation of knowledge. The critical test for the validity of knowledge is not so much formed by positive proof or verification, but by the 'survival' of attempts at refutation or falsification : the so-called 'Falsification Principle' (see Popper, K.R., 1934) . Through falsification testing, we obtain high-quality information to relatively improve knowledge. " The model is always subordinate to reality and must constantly be tested against it " (Miquel Ekkelenkamp Bulnes, 'How Science Shapes the Truth', NRC, October 13, 2012, O&D p.4-5).

{See also: Proof via 'Falsification Testing'

: Instead of seeking confirmation, prefer to seek refutation.}

(7.9) Gradations in Verisimilitude.It is clear that certain statements, rules, or predictions are 'harder' or 'more certain' than others. Some representations depart less far from reality than others. Thus, there can be gradations in the verisimilitude and thus reliability of human representations. In other words, there are gradations in relativity, and thus also in objectivity. The concept of 'objectivity', when applied to certain data, thus means a relatively high degree of objectivity. There are also some general regularities to be identified in the reliability of different types of information. For example, when we focus more on the generally recognizable properties of a thing - especially the directly sensorily perceptible (empirical) characteristics - our perception is relatively more neutral, not merely subjective, less arbitrary or 'biased', and thus more objective, than what we add from our own associations, beliefs, and emotions. "What is immediately experienced is subjective and absolute .. The objective world, on the other hand, which science seeks to crystallize in pure form .. is relative. .. Whoever strives for the absolute must accept subjectivity and egocentrism, and whoever seeks objectivity cannot escape the problem of relativism." (Wehl, H., 1927/1949, p. 83/p. 116; quoted in: Popper, K.R., 1934/1959, p.111). "As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality. " (Albert Einstein, ‘Geometry and Experience’, lecture before the Prussian Academy of Sciences, January 27, 1921; in: Einstein, A., 1994, Ideas and Opinions, p.233). 8. Objectivity as an Aspiration.

(8.1)

Eliminate the Subjective?If we want to optimize the reliability of our knowledge, it seems obvious to try to eliminate subjective aspects as much as possible - especially everything that makes knowledge more biased and thus less reliable. But as noted earlier, knowledge is primarily subject-determined: entirely free of subjective aspects it can never be. (8.2) A Workable Alternative.Fortunately, there is an alternative: we can strive for knowledge that is as objective as possible. Knowledge or information is more objective if it contains fewer subjective distortions and arbitrary elements. objectivity can thus be an ideal - something to aim for as much as possible. "The question is not whether objectivity as such exists, but to what extent we can approach it." (Otto Neurath, 1931; see also: Cartwright, N., Cat, J., Fleck, L., Uebel, T.E., 1996, p.87) . (8.3) A Practical Criterion: Intersubjectivity.A practical way to pursue this ideal is to make knowledge as intersubjective as possible: that is, based on elements that can be perceived, recognized, and understood in roughly the same way by different people, despite their mutual differences in perception, background, and interpretation. Elements that meet this condition are, for example, directly observable phenomena in reality - especially those that can be perceived through the senses and measured or quantified in some way. "Intersubjectivity is what we have instead of objectivity. " (Richard Rorty, ‘Solidarity or Objectivity?’, in: Rorty, R., 1991, p.23) . (8.4) Objectivity as a Relative Concept.From this perspective, objectivity is thus not an absolute state that is fully attainable, but rather a relative quality that can be achieved to a greater or lesser degree. Reliable knowledge is then that which most people - at least those with sufficient prior knowledge and good faith - can agree on as a good representation of reality, based on shared observations and experiences.

{Note: See also epistemology: Coherence theory of truth, as well as the

Consensus theory of truth.}

(8.5) Science as Benchmark.From this follows a next step: the more intersubjective knowledge is, the more reliable it becomes - provided it has been sufficiently tested against reality. This striving for intersubjectivity is especially characteristic of science, where knowledge is systematically tested and refined based on empirical data and logical reasoning. Scientific knowledge can thus serve as a benchmark for reliability, without claiming absolute truth. " Science differs from other disciplines not because it alone can arrive at the truth - because it cannot - but because it has reliable methods to approach it." (Miquel Ekkelenkamp Bulnes, ‘How Science Shapes the Truth’, NRC, October 13, 2012, O&D p.4-5). (8.6) A Dynamic Process.The pursuit of objectivity is thus a dynamic process: a continuous effort to improve knowledge by eliminating errors, refining insights, and expanding intersubjective agreement. This aligns with the view of science as an ongoing, self-correcting enterprise, as advocated by Karl Popper and others. "We cannot identify absolute truth, but we can identify error and learn from it." (Popper, K.R., 1963, p.16). 9. Additional Criteria for the Social Sciences.The above principles apply generally to the pursuit of reliable knowledge. However, when it comes to the social sciences, additional challenges and criteria arise due to the nature of their subject matter: human behavior and social phenomena.

(9.1)

Complexity of Subject Matter.Unlike the natural sciences, which often deal with predictable and measurable phenomena, the social sciences study human actions, which are influenced by a multitude of factors - psychological, cultural, historical, and situational. This complexity makes it harder to establish general laws or predictions with the same precision as in physics or chemistry. "The subject matter of the social sciences is so complex that it resists the kind of precision found in the natural sciences." (Isaiah Berlin, ‘The Concept of Scientific History’, 1960) . (9.2) Influence of Subjectivity.In the social sciences, both the researcher and the researched are subjects with their own perceptions, intentions, and interpretations. This introduces an extra layer of subjectivity that is less prominent in the natural sciences. For example, a physicist studying gravity does not need to account for the stone’s opinion, whereas a sociologist studying poverty must consider the perspectives of the people involved. (9.3) Need for Contextual Understanding.To address this, social science research often requires a deep understanding of context - historical, cultural, and social circumstances - which cannot always be reduced to universal laws or simple models. This contextual approach complements the pursuit of intersubjectivity by grounding knowledge in the specific realities of human experience. " Human affairs cannot be understood without reference to the meanings people attach to their actions. " (Max Weber, ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’, 1905). (9.4) Balancing Objectivity and Interpretation.The social sciences thus face the challenge of balancing the pursuit of objectivity with the need for interpretive depth. While striving for intersubjective agreement remains crucial, researchers must also embrace interpretive methods - like qualitative analysis - to capture the richness of human behavior. This dual approach distinguishes the social sciences from the natural sciences and requires additional criteria for reliability, such as transparency in methodology and reflexivity about the researcher’s own biases. (9.5) Practical Relevance.Finally, knowledge in the social sciences is often judged not just by its predictive power but by its practical relevance - its ability to inform policy, improve social conditions, or enhance understanding of human interactions. This pragmatic criterion aligns with the earlier emphasis on utility value but takes on special significance in a field where the stakes involve human well-being. " The value of social science lies not only in explaining the world but in helping us change it for the better. " (paraphrase of Karl Marx, ‘Theses on Feuerbach’, 1845). This means that the capacity for subjective consciousness is a necessary condition for all information that can be known to us. Within subjective information the abstract patterns belong to the mental constructions. Through these patterns, information can substantively relate to a more general reality: this can be the physical domain, but also the psychological, including subjective experience. Information can also be objective to a certain extent in its relation to that reality, in the sense of 'object-determined'. As a result, the subjective content can have a certain 'informative value'. Subjective information can therefore have a certain degree of objectivity, - even if it only relates to subjective experience. In short, the concepts subjective and objective do not necessarily form a contradiction. ]--> |